For a brief moment Soviet cinema was the most dynamic, innovative and creative in the world. Stalinism soon put a stop to that. Four Corners, a gallery and creative photography space a short walk from Bethnal Green tube, is now showing an exhibition showcasing the faint British echo of revolutionary Soviet cinema and photography.

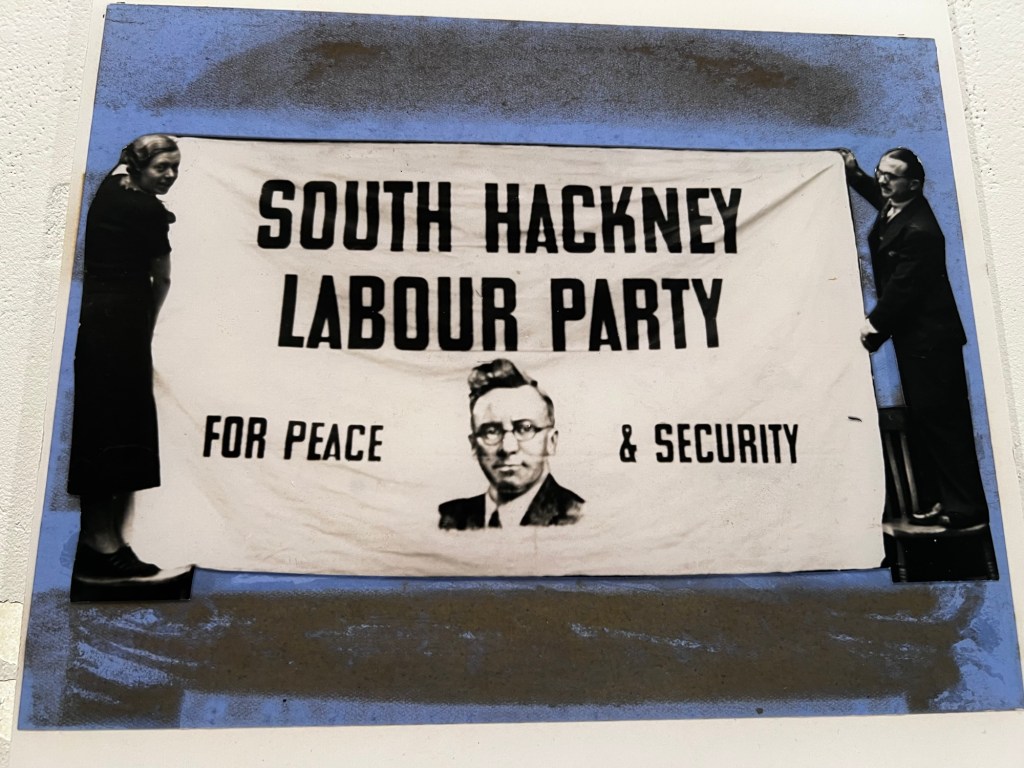

The Workers’ Film and Photo League (WFPL) seems to have been a loose group of photographers and film makers in the orbit of the Communist Party and was part of its popular front against fascism. In fact, it was so committed to the popular front that it chopped “Workers’” from its name in 1935 as it turned away from “class-on-class strategies in favour of a broad social coalition against the rise of the far-right” as one of the notes observes.

For all their popular frontism, they were a dogmatic bunch. In their view “there is nothing entertaining or instructive in the empty, hysterical love affairs of decadent Society women and their gangster or gigolo lovers.” They don’t seem to have seen anything with James Cagney. Their explicit inspiration was Battleship Potemkin or The General Line, Eisenstein’s film about how young Martha organises the peasants into a collective farm and enables them to get a tractor “which definitively determines the victory of the new production methods over the old agricultural system”. As I’ve observed previously, there are still British lefties who write like that.

The WFPL were not able to match Eisenstein. Battleship Potemkin and Strike! are entertaining and instructive. The British comrades made things like Bread in 1934 to expose the horrors of unemployment and hunger. If you are frequently unemployed and hungry you would probably welcome a bit of gangster escapism.

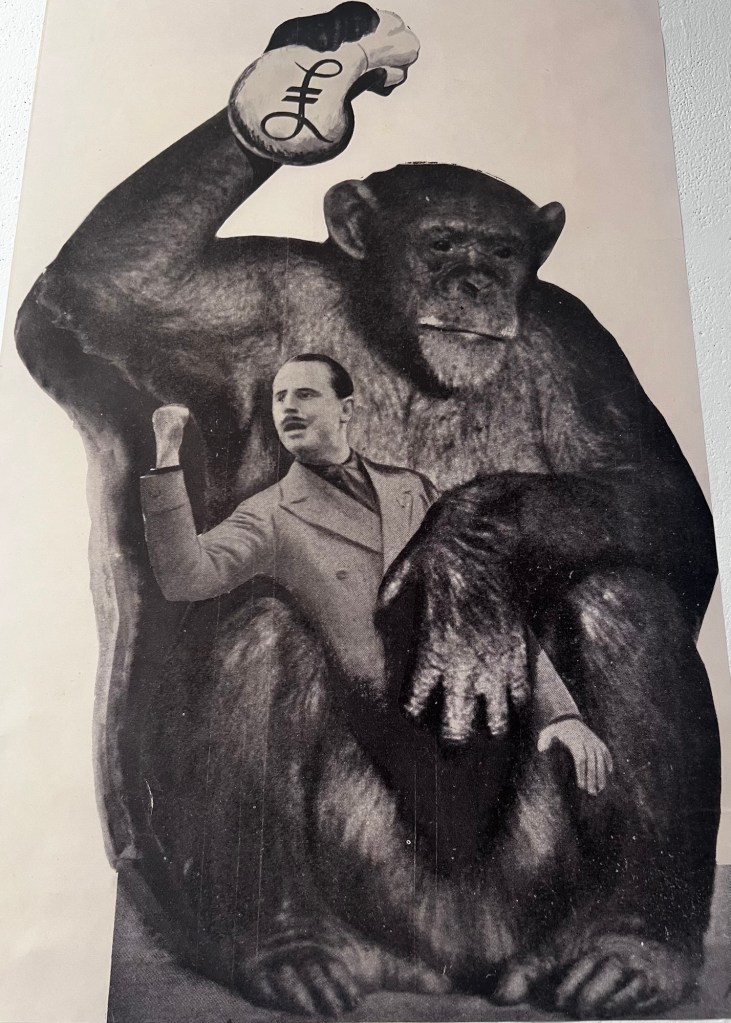

Propaganda was the function of the WFPL and it had a distinctly Stalinist tinge. “There must be joint co-ordinated activity by all working-class film and camera club organisations, all individual workers, students, artists, writers and technicians interested in films and photography.” It wasn’t just hampered by lack of studios and budgets, it very much gives the impression of art being directed by the Party, a surefire way to strangle creativity, especially when you are told “The film is the machine-gun of ideological warfare.”

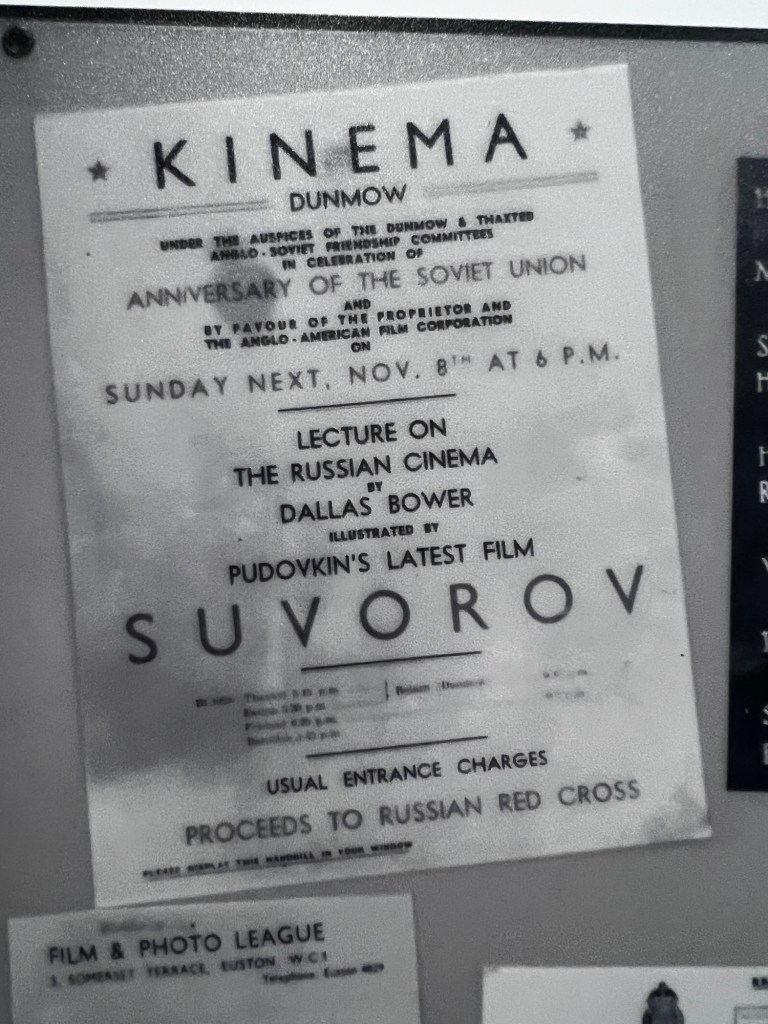

But this was a time when Dunmow, a small town five miles from Stansted airport, had a lecture on Russian cinema to mark the anniversary of the 1917 Revolution hosted by the Dunmow and Thaxted Anglo-Soviet Friendship Committees and British socialists were fighting and dying in Spain. The WFPL was taking advantage of the increasing availability of still and film cameras to try and draw radical artists into the influence of the Communist Party but was also trying to create a working class version of the new artistic medium at a time when working class characters were usually the comic relief.

They were probably twenty years ahead of their time in seeking to present working class life on screen, but they were the precursors of the alternative cultures that followed in the fifties and sixties. This exhibition reminds us that they existed and there is always an appetite for expressly political art. It also reminds us that political organisations shouldn’t tell artists what to do or how to do it.

Leave a comment