When the enslaved people of Haiti rose up in 1791the rebels massacred their white masters. A rebellion led by Nat Turner in Virginia in 1831 resulted in an estimated 60 whites being killed. Spartacus and his comrades started their revolt by killing their owners and trainers. Every slave revolt in history has been accompanied by killing, revenge and an attempt to settle scores. Confine and dehumanise people and when they revolt some of their actions will be an outpouring of rage, violence and a desire to pay back the oppressor in their own coin. What was true in the 18th century is true in the 21st century. Insert your own contemporary reference.

Rise Up: Resistance, Revolution, Abolition has just opened in Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum and runs till June 1st. It’s free, though you are invited to make a donation.

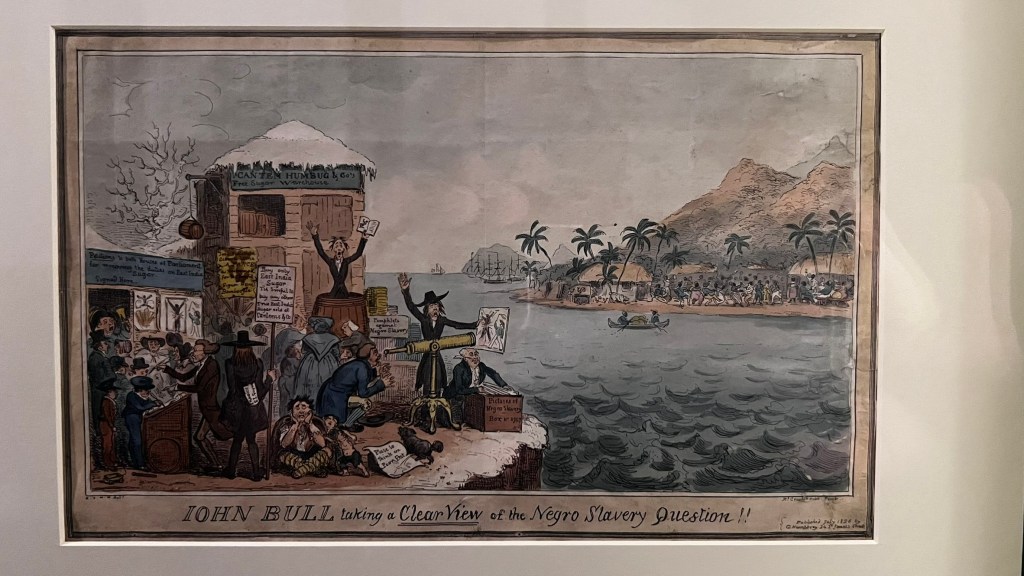

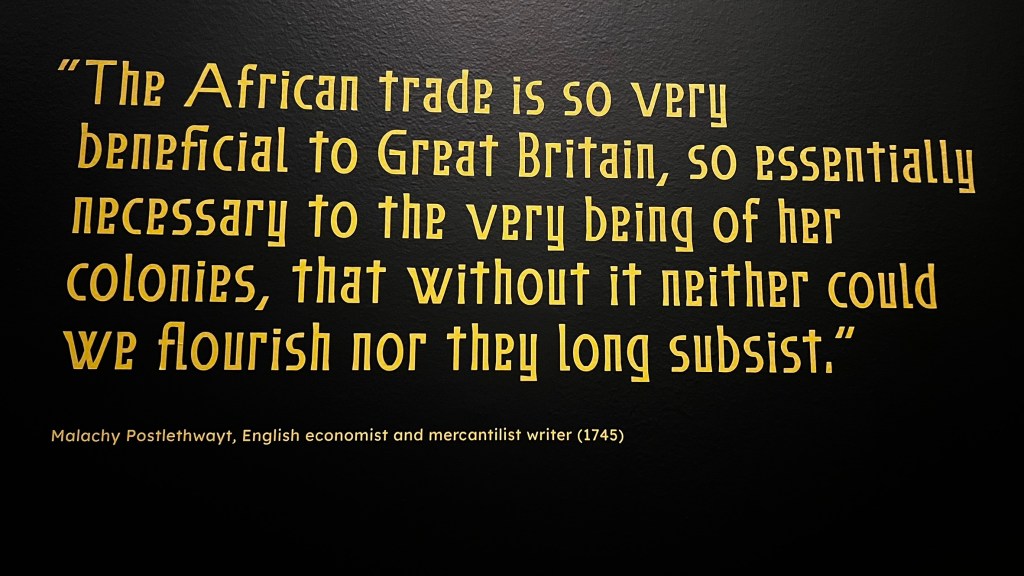

It is a mix of works by contemporary artists who aim to honour the known and nameless rebels and subvert the visual language of the slavers’ artists. This is a slightly controversial approach. Some columnists like Alice Thomson resent the idea that “you are not encouraged to look at the costumes, relationships or beauty, but to judge our history and find it wanting.” Never mind the misery behind the wealth, look at the pretty frock and clever use of colour. However, if Simon Sebag Montefiore, as big a fan of the IDF as you are likely to find, reckons that explaining that British capitalism was built on slavery and murder has become “humdrum”, I say keep on doing it.

The Fitzwilliam has a difficult relationship with the slave trade. Richard Fitzwilliam left the money in his will which allowed it to be established in 1816, but much of the family money had been made through slaving. Though I am sure there will be no shortage of public school educated journalists who would point out that it also paid for a lot of gorgeous outfits, so it wasn’t all bad.

A difficulty facing anyone organising an exhibition about enslaved people is the relative paucity of surviving artefacts, likenesses and first person accounts. This is hardly surprising when the slavers’ attitudes were similar to those of ancient Greece or in a group of Reform members. Part of this gap is filled with imaginings of portraits of women like Marie-Jeanne La Martiniere dressed as a Mamluk warrior.

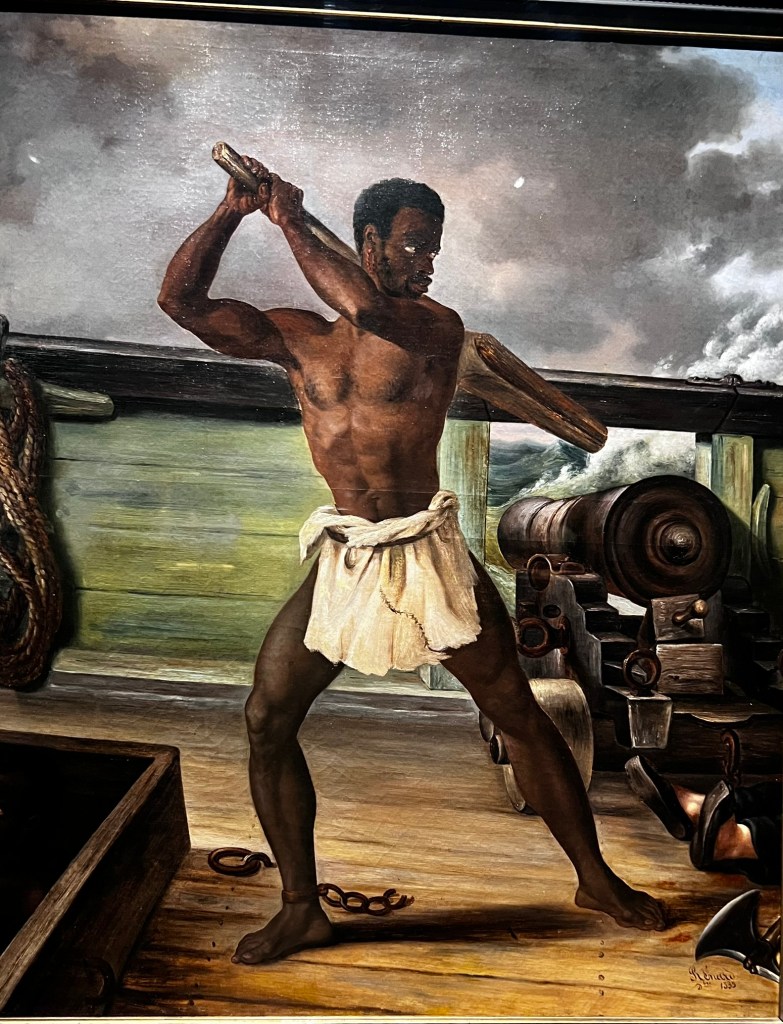

The exhibition just ducks the issue of the violence of slave revolts, glossing it over by saying “resistance took many forms: individual and collective, non-violent and violent”. However, if you look closely at a selection of combs, which were an important cultural artefact in Africa, you will see one with images of severed ears representing the defeat of the British by the Maroon people. Much easier to find is La rébellion d’un esclave sur un navire négrier by Renard édouard-Antoine. It is a shame the museum isn’t selling prints of that as it depicts a rebel on a slave ship who has just floored a crew man. Perhaps we should remember there were victims on both sides in these slave revolts. Or perhaps we shouldn’t and we should always take the side of the oppressed rather than the people who exploit them.

Exhibitions like this are probably illegal in the United States now, as is the surprisingly good Channel 5 (sic) documentary on the Ice Age which sets out the science of climate change. Given that Labour seems determined either to gift Reform the next election or just nick all its ideas, try and catch both while you still can.

Leave a comment