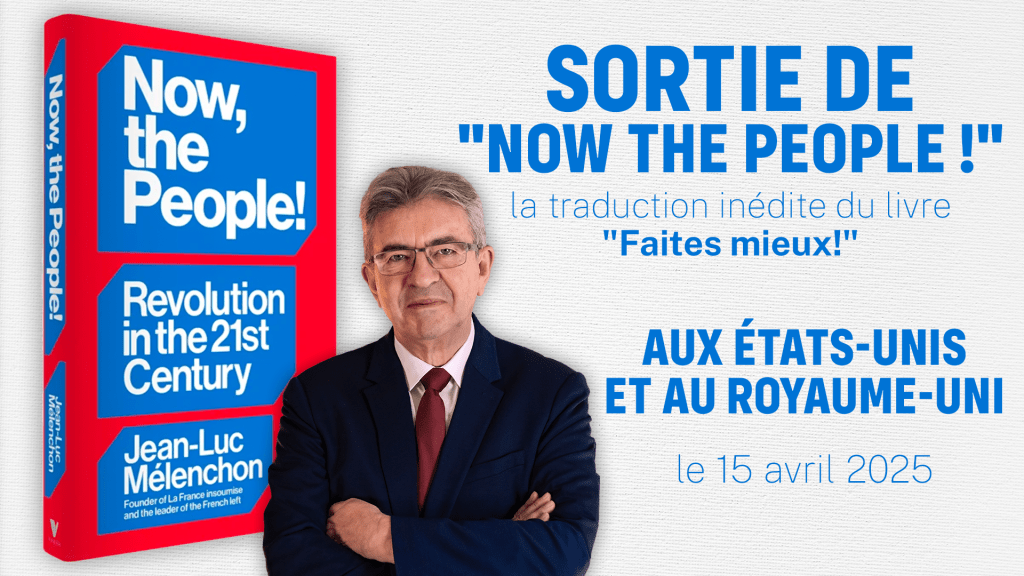

Now, the People! Revolution in the Twenty-First Century by Jean-Luc Mélenchon

Have you ever felt that you were channelling Maximilien Robespierre when you were on the bus? I don’t mean that you have wanted to summarily execute someone listening to music without headphones because you believed them to be an enemy of virtue. More grandiosely, “I am of the people, I have never been anything but that; I despise anyone who purports to be something more.” That’s the thought that came into Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s head when he was recognised on the Paris metro.

His new book Now, the People! Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, gamely translated by David Broder, is a very specifically French twist on trying to pull together a new revolutionary manifesto for a time of huge population growth, apparently inevitable ecological catastrophe and a rapidly intensifying conflict between a declining United States and an ascendant China.

It starts off well enough. Much of the first part is an examination of the ecological crisis and can fairly be described as militantly ecosocialist even if he doesn’t use that word. He rejects the unbridled capitalist productivism which is the nearest thing British Labour has to a programme and correctly attributes the accelerating collapse of the natural world to this relentless search for profit. It is a bit harder to follow his thinking when it comes to his proposed solutions. Suggestions like “we need to create a new society, based on recognition of the inescapable need to confront the consequences of climate catastrophe” say nothing about how this is to be done. It is this reluctance to properly describe what a modern revolution might look like which is the book’s major weakness. More on this later.

Mélenchon is without doubt an internationalist. He takes us on a whistle stop tour of the major radical upsurges of the last twenty years or so from Sudan, Iran, Greece, Egypt, Ecuador to Thailand, but doesn’t make the obvious point that none of these movements were successful. His phrase is “citizens’ revolution”, but while these risings sometimes created governmental crises at no point, with the possible exception of Greece, did they offer the possibility of one class removing another from power.

No class

In fact, class is a peculiar blind spot for Mélenchon. As David Broder points out in his foreword Mélenchon’s party La France insoumise (LFI) “tends to relativise the traditional socialist idea of the working class as the central actor in transforming society.” That is rather an understatement. The existence of a large and changing working class is acknowledged and described but Mélenchon insistently refers to “the people” in a way that owes more to Robespierre than Marx. This seems to be due to Mélenchon’s particular view of France as being in some way eternally unique among nations by virtue of its post 1789 revolutionary heritage. He pushes this to absurd limits arguing that “France is a power with a universal calling…It can be a unifying and inclusive force along with the many nations on the continents that share its shores”.

It is that view of the special character of France and the French that allows him to welcome national flags at Gilet Jaunes demonstrations and approving the fact that they forbade discussion of immigration at their events because it was divisive. A more logical view is that when workers are coming into struggle it is the perfect time to try to talk them out of their reactionary prejudices.

Absent from the book is any consideration of what is to be learned from the revolutionary experiences of the 20th century. While it is welcome that he does not want to set up a 1917 reenactment society, there is no reflection of the abomination of Stalinism, the failure of the German revolution, the importance of pluralism and revolutionary democracy. This is clearly a political choice because there is a long section on space and mining rights on other planets, subjects which are undoubtedly important but of limited application when developing a strategic orientation for revolution.

China

Mélenchon has little to say about Russia but is voluble in his enthusiasm for China and its role in creating a bi-polar world. His reasoning for this is idiosyncratic: “never was the world so under control, down to the last corner (sic), as it was in the days of the last Cold War”. It is fair to say he is a Sinophile, and he makes no secret of his admiration for the rapid development of the Chinese economy and military. However, there is not a word about the complete lack of political freedom for the Chinese working class even though he offers a theory of networked citizens which is applicable everywhere else in the world. That said, LFI is not renowned for its vibrant internal culture and Mélenchon overshadows its entire membership.

Now, the People! Revolution in the Twenty-First Century is ultimately a frustrating book which does not live up to the promise of its title. Mélenchon retreats into left social democratic pieties about the potential for good offered by the United Nations and how Brazil, India, Russia China and South Africa offer the potential of an “alter-globalising diplomacy”, a phrase which might mean something in French but is gibberish in English. What he does not do is explain how the working class and oppressed of the world take power away from the class that currently possesses it and is using it to make the planet uninhabitable.

Leave a comment