In the 1970s and 80s most foreigners in Belfast were either British soldiers or revolutionary tourists. Sorj Chalondon, a French journalist working for Libération seems to have combined work and tourism and has written two novels based on his time in the north of Ireland in that period.

Return to Killybegs is available in English and deals with the killing of Denis Donaldson, an IRA member who worked as in informer for the British. By chance, Gerry Adams is currently suing the BBC for libel over a claim that he ordered Donaldson’s murder and has told a Dublin court that IRA membership was “not a path I took”, a claim that will come as a surprise to the dogs in the streets of Belfast.

Mon traître isn’t available in English and is a lightly fictionalised account of how Chalondon became very friendly with Donaldson who is given the rather absurd name of Tyrone Meehan in the book. It is a bit like me writing a novel about a French man and calling him Calais Dubois or Montpellier Leblanc.

However, Chalondon has a good eye and ear for Belfast. Here’s his explanation of his struggle with the accent:

“L’accent de Belfast. Cet incompréhensible, cet impossible des premiers contacts, quand « deux » ne se prononce pas « tou » mais « toïye », lorsqu’une maison est une « haoïse », que « petit » se dit « wee », que « oui » se prononce « haïe », et au revoir « cherioo ».

-Are yee hir feur loooong?”

He really should have included “fillum”.

Chalondon’s character Antoine is a violin maker living in Paris. An encounter with a Breton nationalist gets him obsessively interested in the north of Ireland and he decides to visit the place. Chalondon had to go there for work. He was also involved with a group called Gauche prolétarienne, a Maoist influenced outfit which got into sabotage, burning buildings and attacks on police stations, so you can see why he would become friendly with a man like Denis Donaldson who had joined the Republican Movement in the 1960s and was involved in the heroic defence of Short Strand against an attempted loyalist pogrom. In real life, as in the novel, he was a friend of Bobby Sands.

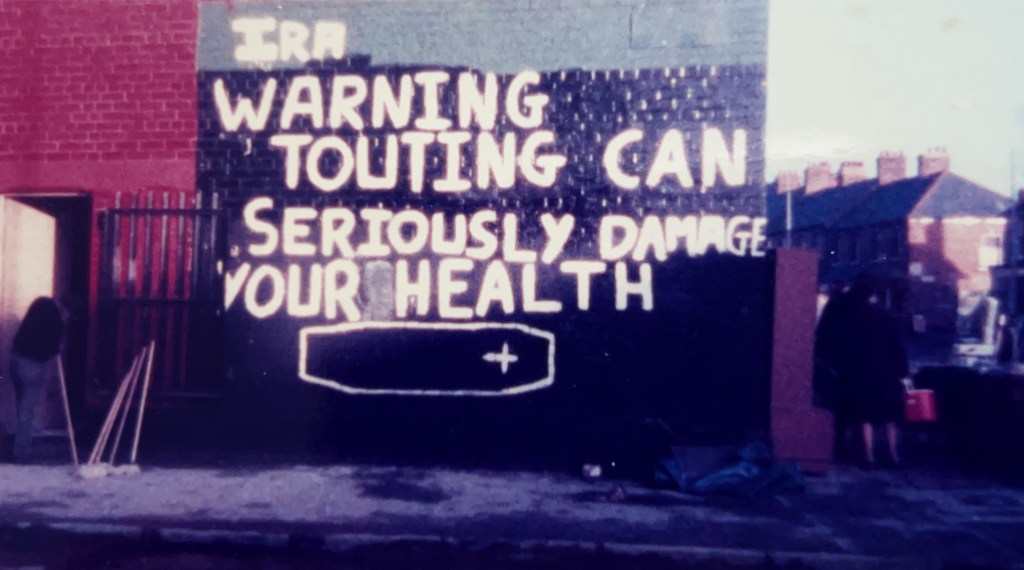

The Belfast of the book is an intensely bleak place. “On the Falls Road, in Divis flats, in Whiterock, in Ballymurphy, in short Strand, in Springfield, in Ardoyne, in the Markets and in Andytown, in these areas of extreme poverty, of an ugly beauty and the violent that terrifies the newspapers, Belfast whispered to me that I was quite at home”. As well as the deep poverty, as evidenced by Meehan’s icy cold, damp home, there is the weather. The sun never makes an appearance but there’s snow, fog and no end of rain. But if he thought Belfast was grim then he should have gone to Derry.

Antoine falls platonically in love with Meehan who introduces him to the smoky Provie drinking clubs of the period. Meehan’s motivation is obvious enough, but we learn nothing of Antoine’s politics beyond his quixotic obsession with a misunderstanding of the Irish revolution. France has never lacked for outlets for anyone with an interest in radical movements, but his is a solitary job and he gives no evidence of interest in French politics.

As part of his service to the IRA, Antoine lets random Republicans crash at his flat, including one called John McAnulty, a coincidence that will amuse anyone familiar with the city’s left politics. By another coincidence, the excellent Belfast Telegraph podcast series this week featured an episode on a member of the IRSP who was tortured and murdered in Paris by his own organisation as it took its first steps towards gangsterism and years of feuding. Séamus Ruddy was the group’s link to other revolutionary organisations and was key to sourcing much of its weaponry.

The reasons for Meehan’s treachery are left as opaque as Donaldson’s, and in common with most British, American and European radicals who cheered on the Provies, Antoine allows himself to be convinced that the ending of their armed campaign, welcome as it was, represented some sort of victory.

Mon traître is readable without having a tremendously strong knowledge of French, though it is surprising that it hasn’t been translated yet and it is written in a style which screams out to be made as a rainy, Irish miserabilist film.

Leave a comment