The Times has generally been functioning as a branch of the press office of the Israeli embassy in London since the Gaza genocide started. It amplifies every talking point, repeats every slander and rarely gives a platform to Palestinian voices. Melanie Phillips, an increasingly verbally violent ethno-supremacist has a weekly column in which she argues Palestinians are a non-people and gives the impression that she does not consider them human at all.

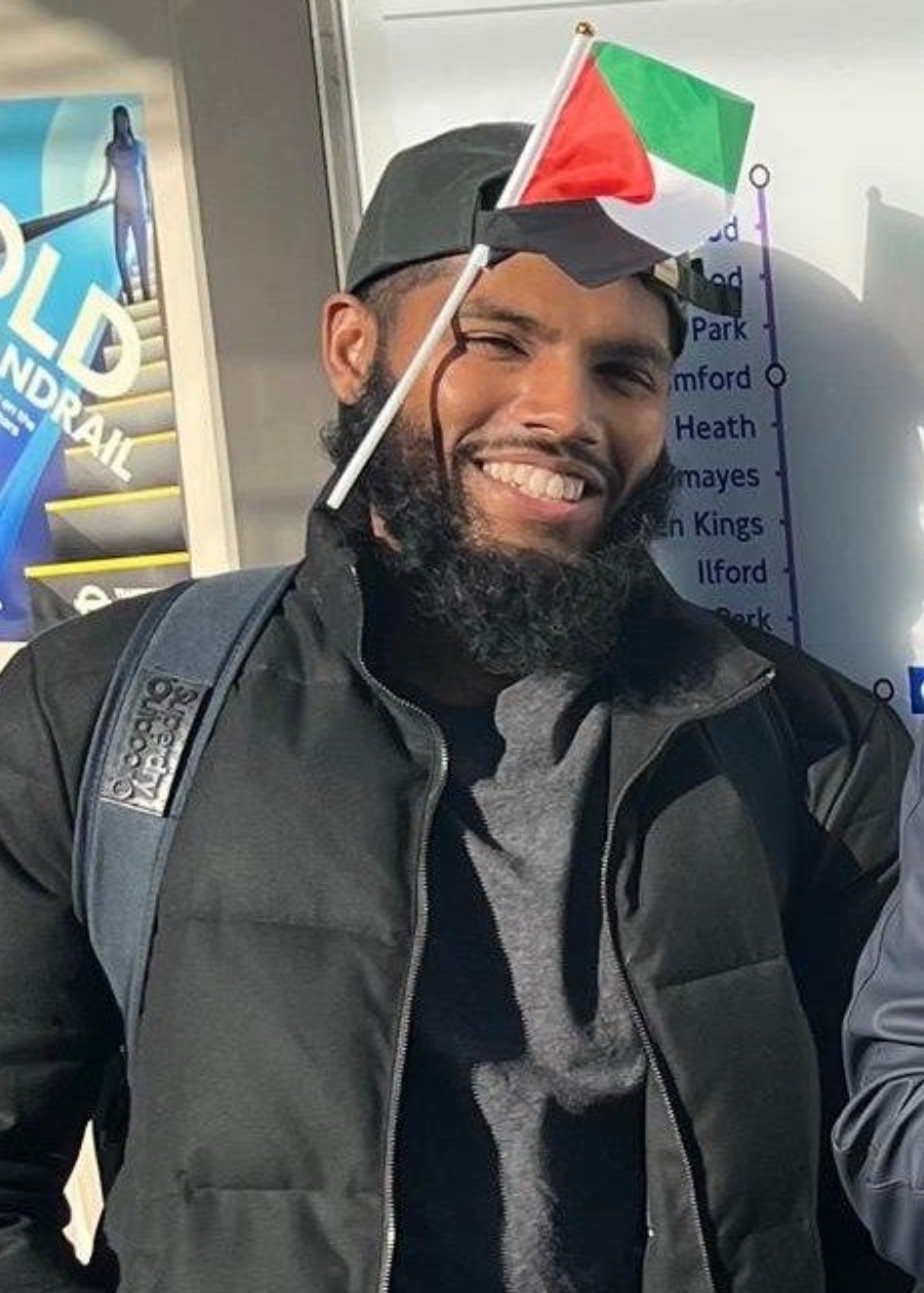

This made the long feature on Palestine Action hunger striker Kamran Ahmed in yesterday’s edition something of a surprise. The paper much more typically runs smear pieces and character assassinations it has been fed on climate and Palestine activists.

Palestine Action’s hunger strike prompted me to read David Beresford’s book Ten Men Dead on the 1981 Republican hunger strike. I have written before about the features the two protests have in common and what makes them different.

The Republican prisoners had a tightly structured military organisation inside and outside the prison; an authoritative external leadership with which they were in daily contact; a justified sense that they would receive a high level of support from their communities and a sense of being part of a long and honourable tradition. The absence of many of these things makes what the Palestine Action hunger strikers are doing all the more impressive.

Kamran was able to speak to journalist Samuel Lovett by phone and it struck me how much he had in common with Bobby Sands.

Kamran is 28 and Bobby was 27.

They both come from working class backgrounds. Kamran is a car mechanic. Bobby was an apprentice coach builder before joining the IRA and in his rare periods of freedom also operated as a Republican community and cultural activist. Of course, a major difference is that Palestine Action have explicitly rejected violence as a way of stopping genocide.

Religion is important for both men. Kamran told The Times that he is reading the Quran and praying. “That’s really getting me through it,” he said. “Honestly, I don’t think I’d have the mental fortitude without Islam in my life.” Irish society was much more religious in the early 1980s and Bobby Sands was a conventional Catholic. He attended mass in prison and wrote “I believe in God, and I’ll be presumptuous and say he and I are getting on well this weather”.

Neither man sought death. Kamran told The Times “Every day I’m scared that potentially I might die” and acknowledges that there will be long term health implications if he does survive. However, he sees the sacrifice as one worth making. This is reminiscent of Bobby Sands, who shut down an argument with a priest by reminding him of the Biblical quote “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”.

Kamran told The Times “I understand it’s going to be difficult for everyone to watch me go through the situation. When I think about my friends and family … it’s difficult to push those thoughts aside,” he said. “But I think it’s necessary to achieve what the world should really look like.”

A common feature of both hunger strikes is Labour’s attitude. Starmer, Lammy and Timpson are willing to let their political opponents die. They are prepared to kill prisoners of conscience. Labour has history here. In 1981the party sent its functionary responsible for the six counties, a footnote of a man called Don Concannon, to visit Bobby Sands a few days before his death and tell him Labour was supporting Thatcher’s strategy to kill the prisoners and break the mass movement.

Kamran Ahmed, Bobby Sands and the other hunger strikers were ordinary people living unremarkable lives until history and events made them feel compelled to sacrifice themselves for their ideas and for other people. You do not have to agree with all their strategic and political choices to acknowledge their inspirational heroism.

Leave a comment